Brief Introduction

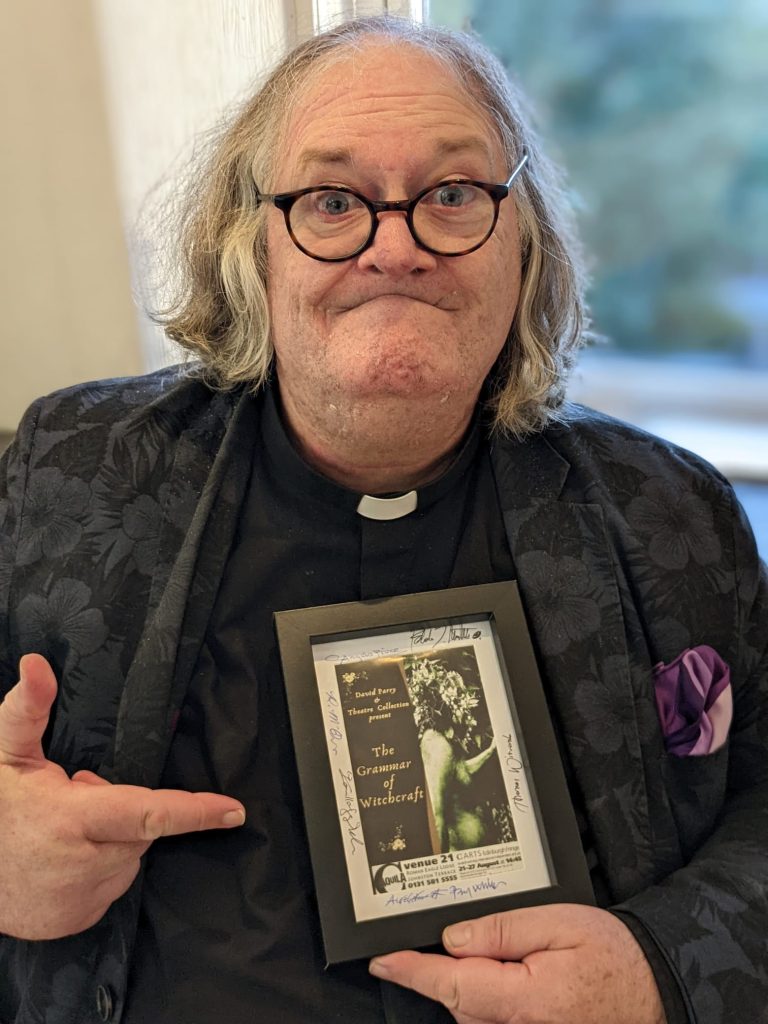

Rev. David William Parry is an Old Catholic priest, poet, and British theatre practitioner, who has traveled widely in Central Asia as well as serving as the first Chairperson for Eurasian Creative Guild. Additionally, he is an elected Fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society, not to mention a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, whose published works include Caliban’s Redemption, The Grammar of Witchcraft, Mount Athos Inside Me, and Women in Mayhem. Currently, he lives with his husband on an island in the Inner Hebrides.

London Post:Hi Rev. David, thank you for talking to London Post. How did it feel to take The Grammar of Witchcraft to Edinburgh Festival Fringe and C venues last August (2023)?

David William Parry:I was very honoured to engage with the energy pulsing around Edinburgh last year. Said so, I am something of an Edinburgh Fringe regular. Indeed, I directed and co-produced the comedy,Shakespeare Tonight, back in 2016, while I have occasionally performed in experimental productions as an LGBT activist in the past. However, staging my own play was an entirely new and exciting experience, particularly since I could revisit old themes, as well as explore my obsession with Surrealism. Secondly, we were upgraded to the C aquila venue, which I personally think is the perfect setting for this dreamlike comedy.

LP:What did bringing a show like The Grammar of Witchcraft to Edinburgh Fringe mean to you?

DWP:The Grammar of Witchcraft was originally published as a collection of LGBT poems with an accompanying narrative. As such, it was one of my experimental texts, wherein I was trying to develop the notion of theatrical poetry or, in other words, the type of poetry which must pass through a character in order to reach an audience. In which case, I could hardly believe my good fortune in getting this show performed in the perfect festival for a production of this nature.

LP: What were you hoping to take away from your Edinburgh experience?

DWP: I know audiences are still looking to be challenged as well as inspired, especially, perhaps, in a cultural climate blurring the boundaries between activism and Arts. Hence, I hoped the actors and I could leave Edinburgh 2023 in the knowledge we had delighted our audiences, perplexed them to the core, not to mention having raised their awareness that we still live in a prejudiced world where queer rights still need to be secured.

LP: Can you tell me a little bit about how The Grammar of Witchcraft came about, what was the inspiration behind this unique piece of writing?

DWP:There are two sources to this text. Primarily, my initial impetus arose from a fascination with the character of Caliban in Shakespeare’s The Tempest. Overall, he struck me as the ultimate misfit due to the fact he could never put a foot right. In addition, I actually witnessed one of the events portrayed in The Grammar of Witchcraft when I went to an ordination in Liverpool and actually heard one of the adult participants say to a child that anything out of the ordinary was evil. Taken together, the mythology of misfits and the transmission of prejudice seemed to me twin themes worthy of the boards.

LP: How much of a role has religion played or impacted your creative endeavours?

DWP: I am an Old Catholic priest. Religion impacts everything I do in the sense that faith has alerted me to the fact life must not be taken at face value, whilst our human search for depth, or as I prefer to say the soul, is often best articulated through Arts. All explaining, probably, why I have previously been involved with ten major productions each of which had a metaphysical, or clearly spiritual, essence. Phrased differently, productions embodying the will to struggle against superficiality, or mundanity, in an attempt to reach the Sublime. In fact, my next work (Women in Mayhem) explores concepts of the Sublime and what they might mean in the type of world around us.

LP: What would you say have been the biggest changes you’ve made to this show since it was performed in London as a part of Camden Fringe?

DWP: Obviously, we kept the essentials of The Grammar of Witchcraft the same. Nevertheless, some of the actors might have found its uncompromising LGBT stance difficult, at the same time as finding our deconstruction between casts and audiences problematic. To be honest, I am sceptical of the whole “immersive” enterprise, even though its attempt to directly engage with everybody present is a necessary pursuit. Anyway, I oppose the current dumbing down of material and its unspoken assertion that modern audiences don’t understand sophisticated ideas. In these regards, we streamlined everything, while emphasising the absurd and funny sides of the play. Certainly, we

wanted people challenged by strong characters and increasingly beautiful scenes as much as entertained. Everything above implying, the pace of the play into something much punchier was the real adjustment.

LP:- If you could describe Caliban in a few words what would you choose?

Short, magickal, malcontented, angry, gay, sexy, and articulate.

What were the challenges you encountered taking The Grammar of Witchcraft to Edinburgh?

DWP: Resources are always an issue, because theatrical visions depend on them to a large extent. Also, we needed to find a cast that could think outside the box and not simply aim at the mainstream. After all, theatre is many things and not merely a form of entertainment. With these factors in mind, we had been very fortunate to find the right director, an exceptionally talented group of actors, as well as a minimalist method whereby these concepts could be shared.

LP: When working with Victor Sobchak, who adapted The Grammar of Witchcraft, how important was the creative collaboration between you both when trying to realise the ideal you originally had for a production?

DWP: I have always admired Victor as well as his artistry. He is an unacknowledged giant on the British theatrical scene, as well as an exceedingly talented playwright himself. Altogether, components in our professional relationship, which made our collaboration very easy. Yet, I need to confess as someone who had worked as his creative director in a previous production, this artistic alliance had an almost clairvoyant atmosphere. There were times when he seemed to be reading my mind and finishing my sentences as much as I was doing the same to him. Occurrences making me honestly comment there is genuine magick in this play on a number of levels.

LP:Have you always had a passion for theatre and writing?

DWP: Overall, William S. Burroughs struck me as correct in saying a writer just writes. If I don’t write I feel anxious and grumpy, and am not David. Undoubtedly, David, at the risk of addressing myself in this abstract way, must write in order to be fully David. So, psychology recognised, I cannot recall a time when I did not put pen to paper, or finger to keyboard, with a view to presenting my output in a theatre. For me, theatre is a temple of dreams and nightmares, a holy shrine wherein we can examine ourselves as human beings, alongside those living energies which form us, our history,and the entire continuum. In fact, my calling as a pastor and the provocation offered by Theatre meet for me in the medium of sacred performance, although I have yet to write, or direct, a full production of this type.

LP: What does The Grammar of Witchcraft say about you and the type of theatre you want to make?

DWP: For years I avoided talking about The Grammar of Witchcraft and what it means to me. All in all, I would avoid these types of conversations because it was a very personal outpouring of injustice for me as a gay man, besides being an intuition that poetry loses its magick the minute it is explained.

Nonetheless, homophobia is growing again, whereas prejudice is raising its vile and ugly head anew. Suchwise, I can now openly say The Grammar of Witchcraft is based on the experience of LGBTQ people as witches, gargoyles and monsters in nearly every Western society. We are always excluded, hardly ever given a chance to lead an equal life and are reduced to struggling for basic legal recognition. A sad and continuing realisation making me want to re-embrace the Theatre of the Absurd with an angry twist. Taken together, enough really is enough, whereas it strikes me this is the right time for a “Theatre of Indignation” to examine our raw emotional responses as animals touched by the Divine.

LP: Do you have any advice, tips or suggestions you would offer anyone thinking about getting into theatre, writing or religion?

DWP: Theatre is a minefield, but glorious, beautiful and utterly fulfilling. If you have the bug, get involved. Regarding writing, I have always believed everyone has at least one book inside them, so get to work, since it won’t write itself. In terms of religion, this is Goodness, Beauty, and Truth in themselves. So, find the Transcendental interior to you, search for the secrets of the Overself and become acquainted with the blissful kisses of angels in the Realm of Light that constitute everyone’s Evolution. For me, of course, all of these things unite on a stage, which is why I recommend an exploration of performance by everyone who takes arts and entertainment seriously.

LP: And finally, what did you want your fringe audiences to take away from The Grammar of Witchcraft?

DP:A sense of truth, a thirst for justice and an obsession with theatre. Each partnered by a realisation that fringe is alive and well, and still occupies a necessary and vital place within our industry. At the end of the day, there must be somewhere to test our ideas, amuse each other, as well as deal with the risk of unprecedented fantasies that point to disturbing facts. So said, without the fringe these possibilities become fewer and further between, which is why I sincerely hoped our audiences saw the intrinsic value of our show. Undeniably, whether week one or week three, the Edinburgh Festival Fringe is a unique opportunity for actors and audiences alike to recover the sorcery of performance, meet recognised stars, or discover those actors who are rapidly rising across the firmament, as well as get an insight into the future of performance generally.