By Dr Majid Khan (Melbourne):

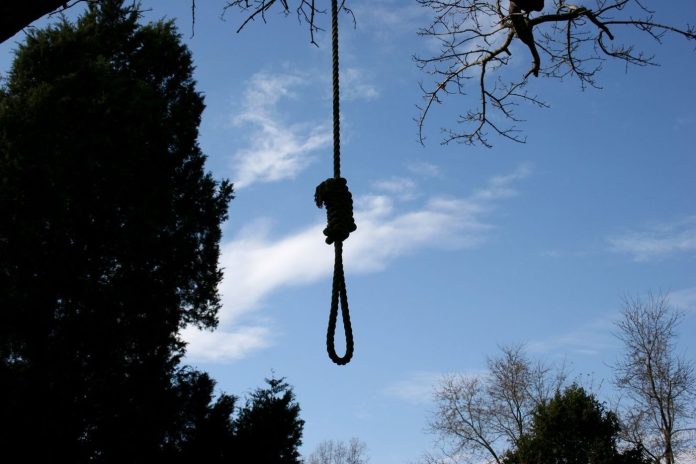

Beneath the narrative of Africa as a continent of vibrant growth and resilient spirit lies a silent, escalating public health crisis: a tragically high suicide rate. While the world rightly focuses on combating infectious diseases like HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis, a parallel epidemic of despair is claiming thousands of lives, particularly among the youth and the elderly.

This issue is more than a collection of personal tragedies; it is a symptom of systemic failures with profound social and political consequences that threaten to undermine the continent’s stability and future prosperity. Understanding this crisis requires a deep dive into its root causes and the ripple effects it creates across societies and governments.

The World Health Organization consistently reports that the African region has one of the highest suicide mortality rates in the world. The numbers are staggering: suicide is the fourth leading cause of death for young people aged 15-29 in Africa. This statistic represents a catastrophic loss of human potential a generation of future leaders, innovators, and caregivers lost to despair. The rates are also alarmingly high among elderly men, who often face isolation and a loss of purpose. This crisis cuts across age and gender, but its drivers are deeply embedded in the social, economic, and political fabric of the continent.

The Crushing Weight of Socioeconomic Despair Persistent poverty and a lack of economic opportunity form the bedrock of this crisis. Africa has the world’s youngest population, and each year, millions of young people enter a job market that cannot absorb them. The chasm between their aspirations, often fueled by education and global connectivity, and the harsh reality of unemployment and underemployment, breeds a profound sense of hopelessness, inadequacy, and frustration. This economic precocity is not just about a lack of income; it is about a loss of dignity and the inability to build a future or provide for a family, which are central pillars of personal identity in many African cultures.

The Lingering Trauma of Conflict and Displacement: Large swathes of the continent are affected by protracted conflicts, terrorism, and political instability. The experiences of violence, displacement, witnessing atrocities, and losing loved ones inflict deep psychological wounds, leading to high rates of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety. The constant state of insecurity and fear erodes the social and communal bonds that are essential for psychological resilience.

The high suicide rate is not just a health statistic; it has deep, corrosive effects on society itself. The loss of so many young people represents a direct drain on the continent’s most valuable resource: its human capital. This “brain drain” through death depletes the future workforce, diminishes innovation, and weakens the civic and economic potential of nations.

The Cycle of Trauma: Every suicide sends shockwaves through families and communities, creating a legacy of trauma. Survivors, particularly children, are at a significantly higher risk of experiencing complex grief, depression, and suicidal ideation themselves, potentially creating intergenerational cycles of mental health challenges.

Strained Informal Support Systems: When formal mental healthcare is absent, the burden of care falls entirely on families. This can lead to caregiver burnout, financial strain from trying to support an unwell member, and sometimes the scapegoating of the individual, further exacerbating the problem.

Reinforcement of Harmful Stigmas: The silence around suicide reinforces the very stigmas that cause it. When a death by suicide is explained away as “spiritual” or hidden as an “accident,” it prevents open conversation and education, keeping the community trapped in a cycle of ignorance and fear.

The suicide crisis presents a direct challenge to political stability and governance, even if it is rarely framed as such. At its core, a youth suicide epidemic can be interpreted as a failure of the social contract. When a significant portion of the population, especially its youth, sees no future and feels that the state offers them no opportunity, security, or hope, it is a profound indictment of governance. This despair can be a canary in the coalmine for social unrest.

Threats to Stability and Security: A large population of disaffected, hopeless, and idle young people is a fertile recruiting ground for extremist groups, criminal gangs, and political militias. These groups offer a sense of purpose, belonging, and economic sustenance that the state has failed to provide. In this way, mental despair can directly fuel political violence and instability.

Economic Consequences: The World Economic Forum has consistently highlighted that mental health disorders are a leading cause of lost economic output globally. In Africa, where economic development is a paramount goal, the productivity losses from untreated depression, anxiety, and the tragic loss of life through suicide represent a significant drag on GDP and national development.

A Litmus Test for Development Agendas: The inclusion of mental health in national health policies and budgets is a key indicator of a government’s commitment to holistic, human-centric development. The current neglect of mental health signals a prioritization of physical health and infrastructure at the expense of psychological well-being, an approach that is ultimately unsustainable.

Addressing this crisis requires moving it from the periphery to the center of public policy. Governments must dramatically increase domestic funding for mental health, integrating it into primary healthcare and national health insurance schemes. Given the shortage of specialists, training community health workers, teachers, and religious leaders to provide basic mental health first aid and referrals is a critical, cost-effective strategy.

Large-scale public awareness campaigns, leveraging radio, social media, and community leaders, are essential to normalize conversations about mental health and frame it as a medical issue, not a moral failing. Ultimately, suicide prevention is linked to broader developmental goals. Investing in job creation for youth, social safety nets for the elderly, and conflict resolution is a form of upstream suicide prevention.

Strengthening vital registration systems and funding local research is crucial to understand the unique nuances of the problem in different cultural contexts and to design effective, localized interventions.

The high suicide rate in Africa is a deafening alarm bell. It is a complex manifestation of interconnected failures in economic opportunity, healthcare access, and social support. The social ramifications fracture communities and erode human potential, while the political ramifications threaten stability and reveal deep flaws in governance. To ignore this silent epidemic is to jeopardize the continent’s most precious asset its people. Breaking the cycle requires a courageous, multi-sectoral response that combines robust healthcare investment with destigmatization, economic empowerment, and a renewed commitment to the social contract. The well-being of Africa’s future depends on it.

Sources:

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2021). Global Health Estimates: Suicide.

- World Health Organization. (2022). Mental Health Atlas 2020.

- World Bank. (Various Reports). Youth Employment in Sub-Saharan Africa.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Global Study on Homicide.