CANBERRA (AAP) Dr Mjid Khan- Australian researchers have discovered a way to make electricity from thin air using enzymes that can mistake batteries for dead ones.

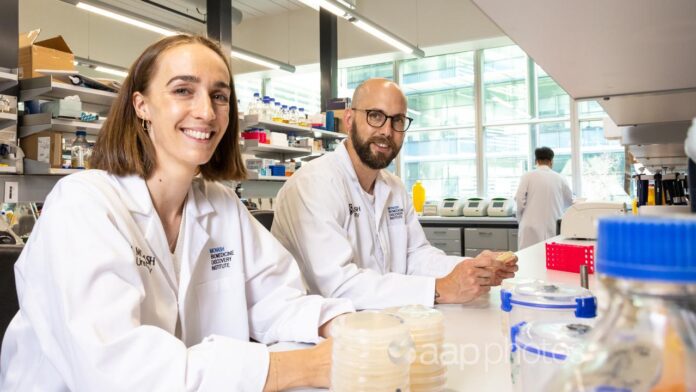

The hero at the heart of the Monash University discovery is a hydrogen-eating enzyme derived from common bacteria found in soil.

And it brings the ultimate goal of a battery-free, air-powered personal device one giant step closer to reality.

This discovery began several years ago with the work of Professor Chris Greening. Professor Greening discovered that some bacteria living in nutrient-poor environments use the small amounts of hydrogen in the atmosphere as an energy source.

“But I never knew how they did it,” said Professor Greening. The “how” is an enzyme called Huc that the researchers were looking for, based on Professor Greening’s work.

The enzyme was then isolated and extracted from a soil bacterium called Mycobacterium smegmatis, and subsequent testing showed that Huc converts hydrogen gas into streams that can power tiny circuits.

The next step is to figure out how “natural batteries” can be used to power devices.

Rhys Grinter, who leads the postdoctoral research team, says it makes sense to start with devices that require a low-voltage, constant power supply.

“For things that are passive in the air, I envision it being devices like medical sensors, wearable exercise monitors, watches, or even tiny computer circuits,” he said. There are also industrial applications such as powering implantable medical devices and remote sensing devices.

Dr. Grinter doesn’t think the enzyme will be a viable way to generate large amounts of electricity.

“If you’re talking about things like power plants, I think the amount of enzymes we can make at the city or city level is too little. There are other solutions that are more economically viable.”

However, its application could still be huge with further research and development.

One of the biggest potential benefits is moving away from batteries that consume precious resources such as rare earth elements.

Research in PhD student Ashleigh Kropp’s lab also shows that the Huc has what it takes to withstand tough situations. “Enzymes can be frozen or heated to 80 degrees Celsius and retain their ability to generate energy reflecting how they help bacteria survive in the most extreme environments. ‘ she said.

Bacteria that produce enzymes like Huc are widespread and can be grown in large numbers, facilitating access to sustainable enzyme sources.

And money, not time, could be the determining factor in how quickly this technology hits the market.

“It depends on the amount of resources we can get for this research,” said Dr. Grainer.

So far there have been some investments from the federal government, but rapid development means finding enthusiastic investors. “Once we do further work, we are looking for investors or companies interested in this technology.

“If we can do that reliably, I think we’ll have something in 10 years.”

Dr. Grinter likes to imagine how Apple applies this technology to its wearable products.

“I like to think about it,” he said.

Wednesday, February 18, 2026

More

© London Post, All Rights Reserved by Independent Media Group UK Limited.