Speaking at the 67th session of the UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs in March, Zafar Samad – director of the Narcotics Control Agency under the President of Tajikistan – admitted that vast quantities of drugs are being smuggled to Europe and Russia through Tajikistan’s “northern route.” In other Central Asian nations, increased efforts are being made to curtail the problem. Kazakhstan, for example, is strengthening its legal systems and policies to effectively counter the laundering of proceeds from drug trafficking in cooperation with the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). The Kazakh government also recently approved a Comprehensive Plan to Combat Drug Addiction and Trafficking. Given its long and porous border with Afghanistan, however, the problem in Tajikistan remains acute.

“The increase in the volume of drug seizures in Tajikistan indicates that there are large stocks of drugs in the northern provinces of Afghanistan intended for shipment along the northern route,” Samad stated. Smugglers are “assessing the situation and exploring the possibilities of transporting drugs into Tajikistan, taking into account the measures taken by the Tajik Government to strengthen the Tajik-Afghan border by creating new border facilities.”

This year will see the adoption of a CSTO program aimed at fortifying the border between Tajikistan and Afghanistan. However, the “northern route” – sometimes called the “Heroin Highway” – has a long and checkered history, which has not always led to interstate cooperation.

The Pamir Highway route was established in the 1990s, opening up new avenues for suppliers following the collapse of the Soviet Union. Beginning in the Kyrgyz second city of Osh, the highway – the second highest international road in the world – traverses the length of Tajikistan and down through the south of Uzbekistan before terminating in Afghanistan. An estimated 15 tons of opium and 80 tons of heroin are trafficked through Tajikistan each year, the majority passing through the poverty-stricken, self-governing Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast (GBAO) along a desolate mountainous route known locally as Bam-i-Dunya – the Roof of the World.

Said by locals to be older than Rome, Osh is a dusty spread of Soviet-era buildings adorned with satellite dishes and murals of MIG fighter jets and Misha the Bear. Having long been dubbed one of the drug capitals of Central Asia, Kalashnikov-wielding soldiers guarded cafés after dark.

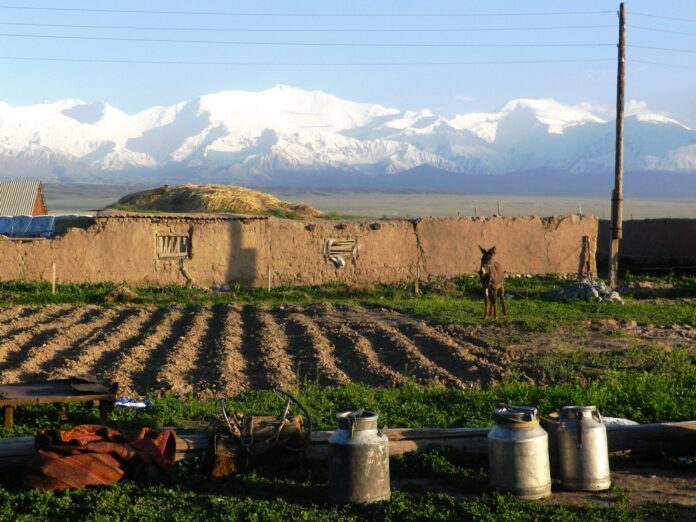

An ancient Silk Road route in use for millennia, the modern Pamirsky Trakt was completed in 1937. From Osh, the red soil highway ascends to the windswept mud-brick hamlet of Sary Tash, a major stopover on the smuggling route where the roads to Kashgar in China and the border with Tajikistan converge.

Despite covering 45% of its landmass, the self-governing Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast (GBAO) is home to just 3% of the population of Tajikistan.

The only Central Asian country to have descended into civil war following the collapse of the USSR, the Pamiris chose the losing side, with the five-year-long conflict leaving approximately 100,000 dead and 1.2 million displaced. The inhabitants of the GBAO have faced privation and persecution ever since, only surviving mass starvation during the 1990s because of humanitarian aid. The region still suffers from crippling poverty, an unemployment rate of around 30%, and an economic exodus of those in search of gainful employment.

One of the most remittance-based economies in the world, in 2023 official figures released by the Ministry of Labor, Migration and Employment of Tajikistan – often underestimated – stated that 652,014 people left the country to work abroad, largely to Russia. According to the World Bank, in 2022 remittances made by migrants accounted for 51% of the country’s GDP.

“The circumstance in the long term can be catastrophic, because you’ve connected the local economy with the Russian economy, so if there is a downtown in Russia, that will impact in a disastrous way,” Dr. Luca Anceschi, a Professor of Eurasian Studies at the University of Glasgow told TCA. “Another problem, he fact that these people tend to settle leads to wider issues. This is something which could prove detrimental in the longer term, a brain-drain if you will, or a loss of manpower.”

Whilst many of these economic migrants are housed in appalling conditions overseen by gang-masters and live in fear – especially in the wake of the recent terrorist attack on the outskirts of Moscow – others, as Dr. Alexander Kupatadze, a Senior Lecturer at King’s College, London, told TCA, are “heavily involved [in smuggling]. According to Kyrgyz Drug Control Agency officials I interviewed, at the time the leader of the Tajik diaspora had been laundering money by purchasing real estate and restaurants in Egypt and Dubai, as well as investing in agriculture in Austria.”

Skirting the border with China’s troubled Xinjiang province, the highway runs adjacent to a barbed wire fence for hundreds of miles. Parts of the fence sagging or missing altogether where wooden struts have been stolen, tire tracks speak to illegal entries and exits. The ground smattered with the skulls of ibex, a ghostly air of desolation permeates settlements here, which are cut adrift by snow for up to nine months a year, with winter temperatures falling to-45°C.

Circumnavigating landslides, a twenty-hour drive brings one from the long-troubled border with Kyrgyzstan to the regional capital of Khorog, population 30,000. In July 2012, fighting broke out here after the Regional Security Chief was dragged from his limousine and stabbed to death. Helicopter gunships whizzing overhead, the authorities severed phone and road links, locals responding by building barricades and calling the government’s actions an invasion. Over a hundred said to have been killed. Riots erupted again in November 2021, following the “mysterious murder” of a local representative. Many here believe that the government’s obsession with regaining control of the GBAO is intrinsically linked with smuggling routes.

Around town, all signs of these conflicts had been plastered over, except for where the bullet holes were too high to reach. On the outskirts, new mansions hugged the hillsides, springing from the scree with manicured lawns and offering easy access to the porous Afghan border. Ostentatious vehicles abounded, the proliferation of flash cars leading to a local saying; it was no longer “How much did it cost?” but “How many kilos did it cost?” TCA asked Kupatadze about government collusion in trafficking. “All large-scale smuggling features some involvement of officials,” he observed, “either in the form of protection, large bribes, or direct participation.”

With monthly salaries averaging just shy of $193 as of November 2023, from the mid-1990s onwards, Tajikistan has seen an explosion of heroin, becoming known as a “narco-state.” In 1997, researchers estimated that half of 18–24- year-olds in the country were employed in the drug trade. As to how high up the criminality goes, in 2000 the Tajik Ambassador to Kazakhstan was arrested in Almaty with 86 kilos of heroin in his car. The next year, the Deputy Minister of the Interior was murdered, the prosecution in the case arguing he’d been assassinated for refusing to pay for a shipment of 50 kilos. In 2014, it was estimated that drug money accounts for as much as 30% of the country’s GDP.

In 2005, when Tajikistan assumed control of its border with Afghanistan from the Russians, heroin seizures decreased by 50%. Piqued by the critical international response, President Rahmon aimed a rare barb at Moscow, alleging Russian complicity in the drug trade. “Why do you think the generals lined up in Moscow all the way across Red Square and paid enormous bribes to be assigned here,” he complained to U.S. officials, ‘just so they could do their patriotic duty?’

In the absence of a legitimate economy though, perversely the flow of narcotics seems to have kept the country from falling apart. “The state is really at the intersection of the benefits and detriment which come from corruption,” Anceschi told TCA. “On the one hand, having the local administration connected with corruption has its benefits, because it’s added a new layer of patronage. So, not only do you have money flowing to the center, but you have another local level, which benefits anyone operating at that level.”

For two decades, the status quo has also served the international community and the U.S. in particular, which needed a stable Tajikistan to ensure uninterrupted flight paths for the so-called “War on terror” in Afghanistan. Infrequent efforts to curb trafficking have also had unintended consequences, with an increase in checkpoints inadvertently disadvantaging smaller operators while allowing cartels to consolidate their control. As Peter Reuter points out, “there are economies of scale in corruption.”

As the highway weaves out of Khorog, dried poppy husks sprout from the roadside. Overturned tanks and buses lay marooned in the Pyanj River, the shores of the 843-mile-long border with Afghanistan just twenty meters away.

This article is reproduce to you by London Post, in collaboration with TCA (Times of Central Asia).