An interview with Rosa Vercoe by Lolisanam Ulugova

In this piece, Ulugova speaks with Rosa Vercoe — former Chairperson of the British-Uzbek Society, independent researcher of Central Asian dance and culture, and higher education professional currently working at SOAS, University of London, and UCL (University College London). Unlike the other interviews in this series, Rosa preferred to keep the conversation in its original interview format, rather than having it turned into an essay.

Q1.Where does your interest in dance stem from?

A. My interest in dance dates back to my early childhood. It felt almost written into my genetic code. I still remember being about four years old, sitting in my grandmother’s flat in Almaty, frozen in awe as I watched ballerinas in white tutus glide across the black-and-white screen of her television in their pointe shoes. That moment left an indelible mark on me.

Throughout my life, I’ve always had a special affinity for dancing. At university in Almaty, I was known as the best dancer at student discos. Sadly, I never had the opportunity to receive professional training or turn my passion into a career.

Life took me through many ups and downs, but my love for dance never faded. Some years ago, I attended an academic conference in Cambridge dedicated to Central Asian culture. During the networking session, one English researcher remarked, “Why has nobody from Central Asia ever presented research on your region’s dance to an international audience? You have such a beautiful, unique tradition, yet it’s absent from academic discussions.”

Her words stayed with me. I decided to channel my passion for dance into independent research and writing. My first article, published in 2018, explored the origins of Uzbek dance through historical sources and interviews I conducted in Tashkent.

During that trip, I met the legendary Gulnara Mavaeva, People’s Artist of Uzbekistan, who passed away on 26 July 2025 at the age of 94. For many years, Gulnara Mavaeva performed on the stage of the State Academic Bolshoi Theatre named after Alisher Navoi in Tashkent, where she played roles in classical ballets. She was an outstanding pedagogue who trained many famous dancers. Gulnara Mavaeva left a profound impression on me. I will always treasure the memories of sitting in her flat, listening to her stories spanning childhood, professional triumphs, and encounters with remarkable figures. Each time I returned to Tashkent, I visited her. Now, sadly, that is no longer possible.

Q2. Your article about Lazgi dance sparked a lot of interest. Why did the Khorezm Lazgi dance attract you so much?

A. My introduction to Khorezm Lazgi came unexpectedly, through watching Dilnoza Artykova on YouTube. A naturally gifted dancer from Khorezm, Dilnoza had trained under the legendary Gavkhar Matyakubova—People’s Artist of Uzbekistan, choreographer, dance historian, and custodian of the Lazgi tradition, whose expertise is recognised by UNESCO.

Dilnoza’s performance struck me with its sunniness, unbridled energy, and celebration of life. I felt compelled to explore the dance’s origins, which led me to literature from Sergey Tolstov’s archaeological and ethnographic expedition (1937–1991). Their research illuminated Khorezm’s fascinating history, cultural diversity, the Khorezmian people’s philosophical worldview, rituals, and beliefs—elements reflected in Lazgi’s movements to this day.

The works of researchers like Djabbarov, Snesarev, and Zhdanko offer deep insight into Khorezmian traditions, some of which persist today. Gavkhar Matyakubova’s scholarship provided an invaluable historical analysis of Lazgi’s dance vocabulary and variations. This is how my love affair with Lazgi began—and why I call it the “sunniest dance on Earth.”

I was privileged to attend both Lazgi festivals in Khiva, in 2022 and 2024, and fell in love with the city and its people. There’s a joy in wandering the streets, chatting with local traders, smelling freshly baked naan and lovingly cooked plov, sipping choi, feeling the desert breeze, soaking in the Silk Road spirit, and feeling the joy of life.

When I heard about the ballet Lazgi: Dance of Soul and Love at the London Coliseum in September 2024, I knew I had to see it. Though a theatrical interpretation by Raimondo Rebeck, a German choreographer, it impressed me with its contemporary choreography, mesmerising set design, music, costumes, and stellar performances by the dancers from Uzbekistan. I even had the privilege of interviewing Nadira Khamraeva, Honorary Artist of Uzbekistan, prima ballerina of the National Ballet of Uzbekistan, for Visit Uzbekistan.

Rosa Vercoe and Nadira KhamraevaThe Lazgi story is still being written and researched. Research into its history and meanings continues, with figures like Gavkhar Matyakubova and Botirov Shanazar of the Shanazm Xorazm Dance Academy working to preserve the dance history and bring the tradition into contemporary performances. Lazgi’s adaptability is what makes it timeless—it speaks to universal human emotions and desires and reminds us of the value of the gift of life.

Q3. How did you decide to write about Tamara Khanum and her adventures in London in 1935?

A. The inspiration came from the book Tamara Khanum – My Life, edited by L. Avdeeva and published in Tashkent in 2009, which I received as a gift from the Tamara Khanum Museum in Tashkent.

Reading about Tamara Khanum’s 1935 visit to London with Usta Alim Kamilov, Tokhtassyn Jalilov, and Abdukadyr Ismailov, I wondered if there were press reviews from that trip. My assumption was correct.

At the British Library, a librarian helped me uncover a short but fascinating Daily Telegraph review from 20 June 1935, accompanied by a photo captioned “Musicians of the Asiatic Russian Folk Dance Group.” This became a key part of my article How They Met Tamara Khanum in London and the Secret of Usto Olim Komilov’s Turban.

My research also took me to the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library, Cecil Sharp House in London, and the Royal Albert Hall Archives, where I found original photographs and documents. Holding these materials gave me goosebumps—Tamara Khanum suddenly felt so close.

BBC Uzbek journalist Ibrat Safo translated my article, and filmmaker Ruslan Saliev later used the images in his documentary The Legends of Uzbek Dance. I also presented my findings at the Lazgi Festival’s academic conference in Khiva in 2022, where they sparked great interest.

Q$. What are you doing in London?

A. I’ve lived in England for over 22 years, having moved here after marrying a British solicitor I met in Kazakhstan. In addition to my Kazakhstan university degree, I pursued two master’s degrees in the UK (one in International Relations and another in Development Studies with Reference to Central Asia from SOAS). Currently, I work part-time at UCL’s Faculty of Brain Sciences and at SOAS School of Arts, where I coordinate the Maqam Project. I enjoy working with PhD students at UCL and collaborating with our small but dedicated Maqam Project team at SOAS, University of London.

Q5.You have been living in the UK for over twenty years. Has it made you feel like a Brit?

A. I first came to London in August 1997, just as news broke of Princess Diana’s tragic death. I witnessed the national outpouring of grief—piles of flowers at Kensington Palace, people quietly queuing to pay respects. This was one of my first impressions of the British public.

Another lasting impression was the British respect for human dignity. I once overheard a police officer address a homeless man as “Sir” while politely asking him to move along.

I admire British values: respect for law, transparency, tolerance for diversity in all forms and cultures, freedom of expression (within respectful limits), and human dignity. While I don’t fully feel British, these principles resonate deeply with me.

My own identity is complex: my mother was Tatar, my father Uyghur, I was born in Turkmenistan, raised in Kazakhstan, and educated in a Russian-language environment. Living in the UK has added another layer to my sense of self. I now see my mixed heritage not as a limitation or disadvantage, but as a strength—it allows me to adapt easily to different cultures. I guess I am a cosmopolitan Central Asian human.

Q6. Please tell us about your work for the British Uzbek Society (BUS)

A. I joined the BUS in 2018 through the late Shirin Akiner, a remarkable scholar of Central Asia with a deep love for Uzbekistan. In 2019, I joined the Executive Committee, working with new Chairman Dr Louis Skyner to promote Uzbekistan in the UK through lectures, cultural events, national receptions, artistic performances, and collaborations with the Uzbekistan Embassy in London.

We hosted talks by diplomats, distinguished academics, artists, and entrepreneurs, including former British Ambassador Chris Allan, Sir Suma Chakrabarti (a former President of EBRD), musicians from Ustazoda Ensemble (Tashkent), dancer Tara Pandeya, Savitsky Museum’s former director Marinika Babanazarova, and contemporary artist Saodat Ismailova, among many others.

During the COVID pandemic, I supported Kamola Makhmudova’s global fundraising campaign Solidarity with Uzbekistan, organising the Dance4Uzbekistan initiative. I invited the young Uzbek dancers to hold online lessons in the most popular traditional dances, like Andizhan Polka, Lazgi, Dilkhorozh, and Surkhandarya dance. Kamola’s online initiative proved to be very popular. Along with other initiatives, it contributed to collecting so much-needed funds to help Uzbekistan during the worst period of the Pandemic.

Kamola was the soul of the Uzbek global community: her energy, generosity, and love for her country were contagious! She left an amazing legacy in developing the unity and pride of the Uzbek diaspora on a global scale.

In 2021, I was honoured with an award in recognition of my contribution to British-Uzbek relations at the House of Lords reception marking Uzbekistan’s 30th Independence anniversary, with the participation of Uzbekistan’s delegation headed by the First Deputy Chairman of the Senate of the Oliy Majlis, Mr Sodik Safoev.

Q7. Please tell us about your plans for the future

A. I plan to continue my work on the UKRI Maqam Project at SOAS, a five-year international collaboration researching maqam traditions from Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Turkey, Iran, and Azerbaijan. In 2026, we will host concerts and workshops by Ilyos Arabov’s ensemble from Uzbekistan, as well as a joint Uyghur-Uzbek ensemble with musicians and singers from Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

The Maqam project is led by SOAS, University of London, in collaboration with Ca’ Foscari University in Venice, and it includes 5 years of intense research, workshops, concerts, and forums. Professor Rachel Harris, the Project Principal Investigator, has put together an international team of the best experts and musicians working on Maqams research and performance.

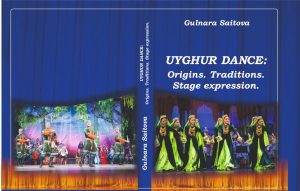

I also aim to research Uyghur dance, an underexplored subject in the UK. Recently, I was invited to review Uyghur Dance: Origins. Traditions. Stage Expression, the most comprehensive study on the subject to date, by Professor Gulnara Saitova. Gulnara Saitova is an Honoured Artist of Kazakhstan, a choreographer, lecturer, and pedagogue, working at the Kazakhstan State Academy of National Choreography and Dance. I look forward to collaborating with her to further illuminate this beautiful art form.

I would like to write about a creative Uyghur community in Kazakhstan. I have recently interviewed Guzel Zakir, the Uyghur visual artist from Almaty. As I continue to delve into Guzel Zakir’s creative work and explore the broader Uyghur community in Kazakhstan, I am excited to shine a spotlight on the talent and creativity of this vibrant community. Through their art and cultural expressions, the Uyghur people in Kazakhstan are not only preserving their heritage but also enriching the cultural fabric of the country as a whole.

Note:This interview is part of a series by Lolisanam Ulugova, a graduate of the Erasmus+ Erasmus Mundus Joint Master Degree (EMJMD) Choreomundus – International Master in Dance Knowledge, Practice and Heritage. The series was created during her professionalisation term at the University of Roehampton. In this collection, Ulugova meets with cultural figures from Central Asia who now live in Europe. These individuals act as bridges between cultures and help promote a deeper understanding of Central Asian heritage abroad.