TINDOUF, Algeria/LONDON/Ali Aouyeche Tindouf/Raza Syed/- Power, fear, technological prowess- symbols that signify nuclear weapons. What is presented as “measures for deterrence and security” often conceal deeper layers of political dominance and colonial ambition under it.

One of the most glaring examples of this is nuclear testing in Algeria by its former colonial ruler- France. These tests were not merely “scientific experiments”; they were acts that perpetuated colonial oppression, caused environmental devastation, and long-lasting health repercussions for the local population.

History of tests: What went wrong?

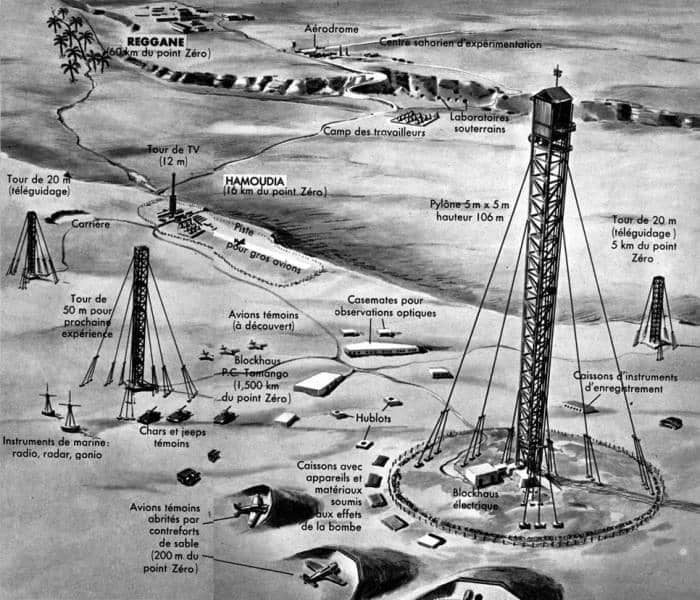

From 1960 to 1966, France conducted a series of nuclear tests in the Algerian Sahara, region they had colonised in the 19th century. Despite Algeria’s fight for independence, which culminated in 1962, France continued to exploit the territory for its nuclear ambitions. This period saw 17 nuclear tests in total, including both atmospheric and underground detonations.

In the Hamoudiya region, for example, on February 13, 1960, France conducted one of the worst nuclear tests in modern history and officially joined the “nuclear club” among many colonial countries at that time.

The colonialism connection

This choice of selecting Algeria as a testing ground was not incidental, but a reflection of colonialism – which at its core, is about control and exploitation. The French nuclear testing in Algeria exemplifies this, as it showed a blatant disregard for the sovereignty and well-being of the Algerian people.

During and after the tests, radioactive fallout contaminated vast areas, affecting local communities who were neither informed nor protected from the hazards. As a result, cases of increased cancer rates, genetic mutations, and other severe health issues have reportedly persisted through generations.

By conducting these tests, France asserted its dominance over Algeria, even as the latter was on the cusp of gaining independence. This act of nuclear testing was a clear message that despite Algeria’s political liberation, France still wielded significant power and influence over its former colony.

The continuation of nuclear testing in Algeria post-independence highlights the inherent racism and dehumanisation within colonialism

Despite various treaties and international pressure to address the consequences of nuclear testing, France has been slow to acknowledge the full extent of the damage or offer adequate compensation and remediation to the affected populations. This reluctance to take responsibility is a continuation of colonial attitudes, where former colonisers often resist admitting and rectifying their historical wrongs.

France’s actions “Complete war crime”

Belaroussi further explained these experiments led to harm to humans and nature, and they certainly amount to acts that could be considered “genocide”, as approved by the United Nations General Assembly on December 11, 1946.

Citizens used as “laboratory rats”

Reggan nuclear testing reportedly resulted in cancer, premature births, deformities, mental disabilities, and miscarriages, and the disappearance of large areas of natural vegetation and various types of wildlife from the bombing area

Ahmed Mizab, a security and strategic affairs expert comments that the nuclear tests in Reggan were mere experiments to measure the intensity of the explosions. He claims that this was which was a process of extermination and execution on them.

These tests led to extensive and irreparable damage, affecting human life, wildlife, and the environment as a whole. They are a crime under law, a violation of international treaties and agreements, as France did not clean the area used for the explosions.

Effects of the nuclear crime persist and hence a strong civil society action is necessary to demand compensation and clean up the affected area of the explosions, without the need for the French government’s consent.

Victims have the right to sue France, and the Algerian state should help them.

The environmental degradation caused by these tests is massive. The Sahara, already a harsh and unforgiving landscape, became even more inhospitable due to radioactive contamination.

There is lack of accountability for the environmental destruction where the natural resources and environments of colonised regions were exploited without thinking about the locals.

French newspaper Le Parisien cited secret documents in 2014 that reveal that much larger areas were impacted by these tests as told by French the government.

Eyes on France to take accountability and action

Sid Amar Al-Hamel, one of the civil society actors in the Reggan region and a defender of the victims of nuclear explosions, said that France’s crimes in the region have left serious damage that is still visible today.

He stressed that by calculating the time required for the effects of nuclear radiation to disappear naturally, the region is still in the first seconds of the disaster.

Congenital malformations in foetuses continue to this day, and many families find it difficult to live with children with them as there is no radical treatment for the diseases spread in the region. Citizens in Reggan still find nuclear waste left behind by France, unaware of the danger it may cause.

Hamel points out that France did not bother to disinfect the experiment area, or even remove the equipment that was the subject of the experiment from residential areas.

He also says that the issue of financial compensation would open the way to the question of who has the right to compensation, given that the negative consequences of nuclear explosions are not limited to a specific time frame or geographic space.

He pointed out that the residents of the Reggan region are today demanding health facilities specialized in treating cancers and various diseases resulting from nuclear radiation, demanding that France bear the consequences of its criminal acts.

It is high time that France steps up in three aspects: acknowledging the existence of nuclear explosions, its leftover waste and identifying its victims.

What next?

Nuclear weapons are not just instruments of war; they are symbols of power disparities rooted in history.True abolition is not just about eliminating the weapons but also addressing the legacies of their development and testing.

The international community has made strides in nuclear non-proliferation, yet the narratives around these efforts often overlook the colonial histories and the disproportionate impacts on marginalised communities.

As the world progresses towards nuclear disarmament, it is crucial to address historical injustices and ensure that the legacies of colonial exploitation are not forgotten. Abolition in real sense must go beyond simply eliminating nuclear arsenals; it requires taking stock of the past and a steadfast commitment to justice and reparations for those most grievously harmed by these weapons of mass destruction.

Key treaty provisions

The First Meeting of States Parties (1MSP) to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) outlines countries to prioritise victim assistance and environmental remediation.

It requires each State Party to provide age- and gender-sensitive assistance, including medical care, rehabilitation, and psychological support, to individuals affected by nuclear weapons, adhering to international humanitarian and human rights standards.

In addition, each state party is asked to take necessary measures for the environmental remediation of areas contaminated by nuclear activities under its jurisdiction or control. These obligations are to be fulfilled without prejudice under international law or bilateral agreements.

This article is produced to you by London Post, in collaboration with INPS Japan and Soka Gakkai International, in consultative status with UN ECOSOC.