By Lolisanam

Based on an interview with Ovlyakuli Khodjakuli, conducted in London on 31 May 2025.

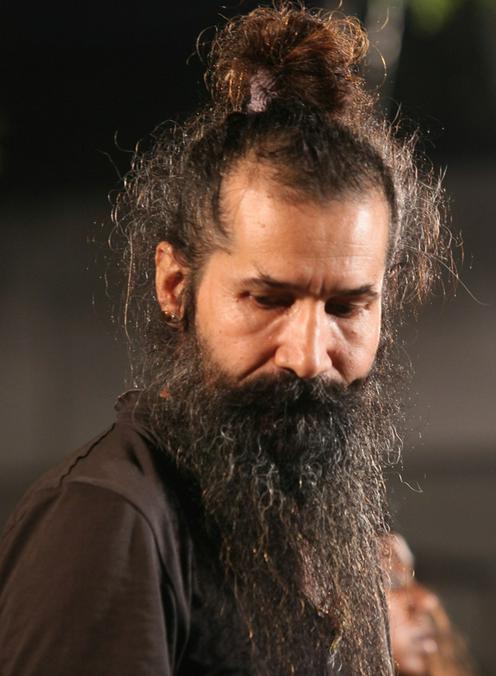

Ovlyakuli Khodjakuli is a well-known theater director from Central Asia. He is famous for blending Russian theater traditions with Central Asian culture. He has directed many plays by writers like Sophocles, Shakespeare, and Oscar Wilde. His work has received praise and awards across Europe. His plays are known for their deep emotions and focus on universal human experiences. Khodjakuli’s goal is to make audiences think deeply and feel personally connected to the performance.

To Khodjakuli, theater has always been a place for confrontation and conversation—a place where actors and audiences challenge each other. He does not see it as a family gathering or a celebration. For him, theater is serious work. It takes presence, effort, and focus. At home, conversations are private and personal. Theater, on the other hand, is his way of speaking to the world. It has been his voice since he was a child, shaped by early life experiences before he even understood the language of performance.

His first connection to theater came through oral storytelling. His father, who had the spirit of a bakhshi—a traditional storyteller—used to tell long epic tales called dastans. He didn’t need a stage. His voice and rhythm turned any space into a world of stories. These were Khodjakuli’s first performances, long before he ever entered a real theater. He didn’t see a live play until he started theater school. Before that, he only knew school performances and theater on TV, which didn’t have the same power as live shows. For him, theater was simple: a performer, an audience, and a shared world made with just a few props.

This idea shaped his early work. For example, he directed a monologue version of King Lear with Turkmen actor Anna Mele. It was raw and personal, influenced by the storytelling of his youth. But when he started formal training, he saw how different his style was from the academic approach to theater. In Turkmen, there’s a phrase orta oyun—which means “play in the middle”—describing folk performance. You stand in the middle, on the ground or on a carpet, and speak directly to people. That was his idea of theater. His teachers didn’t oppose him, but they were often confused by his improvisational style, which came from his memories of desert life. As a child, he made toys from clay—cars, camels, dinosaurs—and gave them life. That early creativity was his first taste of theater.

His father’s performances had a deep impact on him. Even though his father didn’t play instruments, he created rhythms by tapping his hat. He moved easily between storytelling and song, often stopping to explain things to the children. Later, Khodjakuli realized how similar his father’s style was to Brecht’s techniques—changing roles, breaking the fourth wall, using rhythm and song to tell stories. His father was full of joy—always joking and dancing, though his practical mother didn’t always enjoy it. His sister also inherited that joy and became an actress. These early memories taught Khodjakuli that performance is not always taught—it can be passed down through generations.

After graduating from the Tashkent Theater Institute, he returned to Turkmenistan and worked in several regional theaters: the Charjou Musical and Drama Theater, the Sude Theater, and finally the Youth Theater in Ashgabat. There, he directed several plays, including Woman in the Dunes by Kobo Abe, Joseph and His Brothers, Musamman, and Saddala Vanusa, a satire about choosing between two sultans. Although there were no political restrictions, personal life led him in new directions. In 1993, after his son Chingis was born, the theater dormitory was not a good place for a baby. He sent his wife and daughter to Shakhrisabz, Uzbekistan, while he stayed in Ashgabat. That same year, his theater group went to the East-West Festival in Tashkent and toured Finland and Poland, where new creative partnerships began.

One of those partnerships was with Mark Weil and Kamariddin Artykov. They first joked about working together, but it became serious a few months later. Kamariddin was the literary manager at the Abror Hidayatov Theater. Both he and Mark—along with Tapir Yuldashev and Dinara—were leading figures behind the East-West Festival. At that time, traveling between Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan was still easy, so Khodjakuli began working in both countries. But later, new visa rules made that difficult.

Mark Weil made a lasting impression on Khodjakuli. Although he had known of him as a student, it wasn’t until 1993 that he truly appreciated Weil’s vision. Weil had founded the Ilkhom Theater in 1976 during Soviet times—a bold act back then. In 1997, they began work on Oscar Wilde’s Salome, which was staged the next year. Their collaboration continued even after Weil’s death. Khodjakuli kept working with his theater, directing and leading workshops as late as 2016.

In 2011, the Swiss Central Asian Bureau invited Khodjakuli to lead a new experimental theater festival. This became the ARALASH Festival, which included not only theater but also music and dance. Naming the festival was difficult, but they chose aralash, meaning “mixed” in Turkic languages. It made sense to Uzbek and Kazakh speakers, though less so to Tajiks.

By then, the Mavrigi Project had already started. It wasn’t a concert—it was musical theater. The goal was to reimagine traditional music through a theatrical lens. At first, performers—who were used to singing at weddings and public events—didn’t like his approach. But after the first performance in Tashkent, they felt the change. Khodjakuli had spent nights listening to rare ribbon tapes from the 1960s. His father had sung this genre, calling it Mauriki. Listening to those recordings reminded him of maqam, a kind of Sufi music. He removed decorative gestures and focused on stillness and inner feeling.

One of the most memorable performances at ARALASH came from the Tajik group Shams. They mixed traditional and modern music. Their performance went 30 minutes over the planned time, but no one wanted to stop dancing—not even when Khodjakuli signaled from backstage. The energy and spontaneity reminded him of the spirit they had explored earlier in Mavrigi.

One moment stayed with him. During a performance, one dancer stopped moving, while another performer, Mishan Atajan, danced wildly around her. The audience was completely focused. A young man from Tashkent reached out to her in awe. The next day, they learned he had asked to marry her. They were strangers, but both from Mavrik, Bukhara. He wasn’t in love with her personally, but with her image. Through that, he saw something deeper. That is what theater can do—it shows truths beyond words.

When directing such work, Khodjakuli doesn’t give technical instructions. He works by feeling. He once took a dancer’s hands and whispered, “Let the music guide you. Lower your hands. Drop your eyes. Don’t lift your eyelids.” Some later asked if that image—the bowed head, the downcast eyes—was his idea of the perfect woman. In a way, it was. But not in a social sense. In Sufi thought, it stands for longing, humility, and spiritual searching. It’s not about reaching the divine, but moving toward it. That inner search is what keeps people human.

Although he’s not religious in the traditional way, Khodjakuli believes in something higher—call it God, conscience, or a sacred place inside. He tries to keep that space clean, free from greed, cruelty, and lies. That’s what he wants to express through movement and silence. People sometimes laugh—“Mishan says this song is about a chicken or a donkey”—but even Sufi poets used humor to hide deeper truths. The meaning isn’t in the words—it’s in how far a moment or movement can take you inside yourself.

His piece Eske Machit came out in the mid-1990s, after he moved to Tashkent. It reflected the uncertain mood after the Soviet Union collapsed. The group had no fixed cast. They created performances inspired by various sources, including the writer Baev. One of their last big projects from that time was Medea, supported by the Japan Foundation. It was performed in India and Tokyo. It was an international project with artists from Uzbekistan, India, Iran, and Japan. Each country brought something special. India presented Helen. Iran reimagined Oedipus through Jocasta. Japan handled the design. Khodjakuli chose to use Greek tragedy instead of familiar tales like One Thousand and One Nights, because he didn’t want to waste a rare chance on something predictable.

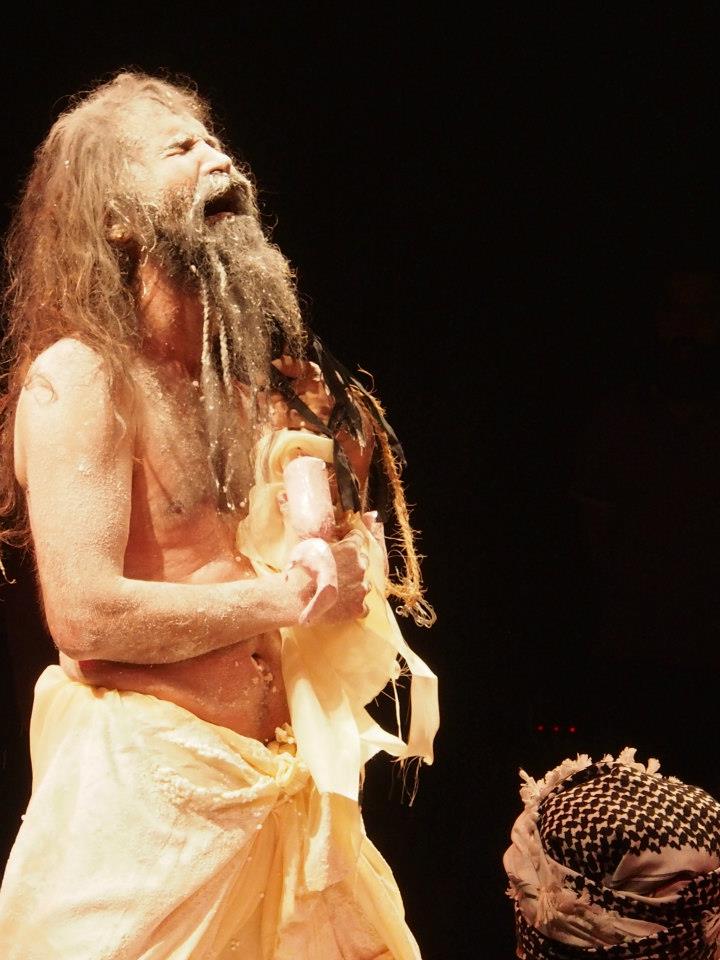

They used only male actors—not for political reasons, but because many female performers couldn’t travel. One famous actress, Sugdujanka, shaved her head and said, “Then I’ll become a man.” She performed among the men with equal strength. Another actor, Asilbek Eshonov, played Glaucus. Later, he asked Khodjakuli to remove a photo online, saying he looked silly. But on stage, he moved like a dove—graceful and transformed. Cameras show one kind of truth. Live theater shows another.

Today, gender, identity, and politics are hot topics. But at that time, none of it was political. Shakespeare used all-male casts. So did ancient Greek theater. For Khodjakuli, it was about the art. He feels a strong connection to directors like Farukh Kasimov, whose work came from poetry, music, and spirit. Kasimov didn’t follow trends. He spoke from the heart. Whether Tajik theater should follow his path isn’t for Khodjakuli to say—but that poetic style fits the region. It asks for presence, not speed. That’s rare in a time of TikTok and YouTube.

Still, some young actors are returning to these roots. That’s how his collaboration with the Kanibadam theater began. They had seen his work in Tashkent and invited him to a director’s lab. Together, they created Vakhanki, then a play combining Hamlet and King Lear with only three actors playing all the roles. They toured India, China, and London. Then, the project ended.

Now, people want simplicity. Even AI can write scripts. But for Khodjakuli, theater is memory—and memory is human. Theater began when humans first mimicked life—hunting, stories, rituals. It will only disappear when humanity does. Of course, it changes. Today, we see Brecht, Artaud, Kantor. He doesn’t stick to one style. His work evolves with society—and with his inner life.

He has started theaters. But he always lets them go. Since 1993, he has chosen freedom—no titles, no fixed teams, no attachments. Because that’s what theater truly needs: lightness, movement, and change.

Note:This is a series of essays by Lolisanam Ulugova, a graduate of the Erasmus+ Erasmus Mundus Joint Master Degree (EMJMD) Choreomundus – International Master in Dance Knowledge, Practice and Heritage. The essays were written during her professionalisation term, which took place at the University of Roehampton. In this collection, Ulugova explores cultural figures from Central Asia living in Europe—individuals who serve as bridges between cultures and work to deepen the understanding of Central Asian heritage abroad.