On September 7, 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping delivered a speech at Nazarbayev University in Astana, Kazakhstan, under the title “Work Together to Build the Silk Road Economic Belt.” In this address, President Xi invoked the historical significance of the ancient Silk Road, tracing its origins back to a Chinese envoy in the 2nd century BC.

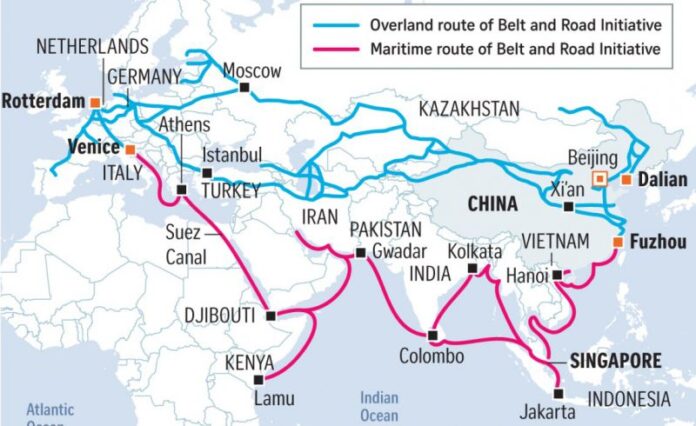

The speech, delivered in its fitting setting, had a specific focus on China and Central Asia, frequently referencing historical connections. Xi Jinping’s original proposal centered on the idea of China and its Eurasian neighbors “jointly building an economic belt along the Silk Road.” This initial proposal was geographically confined, primarily concentrating on China and Central Asia. Moreover, it had a relatively narrow scope in terms of sectors. Xi outlined four areas for cooperation within the framework of the Silk Road Economic Belt, including policy consultation, road infrastructure development, trade facilitation, and the promotion of monetary circulation, particularly trade conducted in local currencies.

One month later, the concept of the Silk Road Economic Belt was supplemented by the “21st Century Maritime Silk Road,” which President Xi introduced in a similar speech before the Indonesian legislature. The Maritime Silk Road, much like its land-based counterpart, was initially limited in both geographic and thematic scope. Xi Jinping’s initial proposal primarily revolved around “maritime cooperation” with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

These humble beginnings laid the foundation for what would later be collectively known as “One Belt, One Road,” eventually rebranded as the “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI) in English, although the original Chinese nomenclature “One Belt, One Road” or “一带一路” persisted. Over time, the BRI expanded far beyond its original vision, extending its reach into nearly every corner of the world. As of the 10th anniversary of Xi’s speech in Kazakhstan, official documents on BRI cooperation with China had been signed by 154 countries, as reported by the official “Belt and Road Portal” website operated by the Chinese government.

The sectors covered by the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) have significantly expanded over time. When President Xi Jinping first outlined this evolving vision during the inaugural Belt and Road Forum in May 2017, he referred to the original four pillars of the initiative: policy connectivity, infrastructure connectivity (which has expanded well beyond the initial reference to “roads” to include railways, ports, pipelines, and digital infrastructure), trade facilitation, and financial connectivity (which now encompasses institutions like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Silk Road Fund, in addition to the use of local currencies). A new dimension was also introduced, focusing on “people-to-people connectivity” through cultural and educational exchanges.

Furthermore, the BRI has given rise to numerous subsets, including the Digital Silk Road, the Polar Silk Road, the Health Silk Road, the Space Silk Road, and the Green Silk Road. From its initial targeted scope, today virtually any collaboration project initiated by China in any part of the world could potentially be categorized as part of the Belt and Road Initiative.

Considering the substantial growth of the initiative since its inception in September 2013, it is essential to examine how the Belt and Road has expanded its global footprint.

The Current Status of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)

As of September 2023, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) boasts a membership of 154 countries, encompassing approximately 80 percent of the United Nations’ 193 member states. This impressive global reach prompts an exploration of those nations that have chosen not to participate in the BRI.

Unsurprisingly, the non-participating countries are notably clustered in specific regions. Notably absent from the BRI are all of North America, a significant portion of Western Europe, and a substantial part of South America.

Beyond these areas, it’s noteworthy that the Quad members, which include Australia, Japan, and India, have opted to stay outside the BRI, each citing their unique concerns regarding China’s global ambitions. In the Middle East, two close U.S. allies, Jordan and Israel, have refrained from joining the initiative. Additionally, there are 15 countries that do not maintain diplomatic relations with China. This group comprises Taiwan’s 13 remaining diplomatic partners, as well as Bhutan and Kosovo.

An intriguing omission is North Korea, ostensibly a close Chinese partner that could greatly benefit from the additional funding that BRI membership could provide. However, it’s plausible that China viewed extending an invitation to North Korea as a high-risk move, with limited potential gains and substantial potential losses. This is primarily due to North Korea’s nuclear ambitions and heavily sanctioned status. In contrast, Iran, another BRI member, also faces nuclear proliferation concerns and significant sanctions but holds a crucial geographic position linking Central Asia and the Middle East.

When examining the regional breakdown of BRI participation, certain patterns emerge. Both Central Asia and Southeast Asia stand out as regions where every state has joined the initiative. In stark contrast, North America remains the only region worldwide where no state has become a BRI member. Sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) regions also exhibit high BRI participation, with over 90 percent of regional countries having entered into BRI agreements with China.