By Lolisanam Ulugova

This interview with one of the most remarkable contemporary artists from Tajikistan and Kazakhstan, Nazira Karimi, was arranged in August 2025. Due to her busy schedule and participation in various international events, it took some time to receive her responses. Nevertheless, it was important to present her answers, as Nazira Karimi’s voice is among the strongest in the region. Through her work and public presence, she makes a significant contribution to increasing the visibility of Central Asian art on the global stage.

London Post:Could you tell us about your path into art and how it all began? Are there any childhood memories connected to your visual practice?

Nazira Karimi: My path to art began almost accidentally. I come from a family of mathematicians and engineers, so art was not an obvious direction for me at first. When I was in high school in Dushanbe, I worked at a radio station called AFM, where I was the only female voice on air at that time. Coincidentally, the radio station shared its office space with a design studio, and I suddenly found myself surrounded by people who were engaged in creative work on a daily basis.

Being in that environment had a profound impact on me. While I was still finishing my final years of school, I made the decision to pursue an education in the arts. From that moment on, things began to unfold quite organically, eventually leading me to where I am today.

As for my childhood, I don’t have particularly strong or romanticized memories connected to visual art. I do remember that I was quite good at drawing as a child, though not in an exceptional or especially conscious way. Art only became intentional for me later, when I encountered it as a possible language and a way of thinking.

LP: How important was formal art education in shaping your artistic practice?

NK: Formal education played a complex role in my life. Before studying at the academy, I spent four years in Almaty, where I studied painting and scenography. Later, in Vienna, I completed both my BFA and MFA in Media Art.

To be completely honest, I initially entered academia largely due to family pressure (which I can now recall with a smile). At the time, I didn’t fully understand how significant this experience would become for me. Living far away from home and navigating a new country, language, and institutional system taught me not only artistic skills, but also how to position myself and think critically about my surroundings.

Academically, I am deeply grateful to certain individuals, such as my professor Constanze Ruhm, whose support and intellectual generosity were truly important for my development. At the same time, I have to acknowledge that European art academia as a structure is deeply problematic. It is profoundly Eurocentric and often openly or subtly racist. As a non-European artist, you are constantly confronted with this reality during your studies, and it inevitably shapes you.

Did it help me move forward in my artistic practice? Yes, but not in a straightforward way. Academia gave me time, access, and a framework, yet it also forced me to articulate my own position in opposition to many of its norms. In this sense, it helped me clarify my

LP: Looking across the projects on your website, what are the core ideas and questions that run through your practice, and which media do you primarily work with?

NK: Rather than speaking about each project separately, I see my works as part of one continuous research process. Across different formats and over the years, my practice consistently engages with questions of collective memory, grief, and the environmental of Central Asia, particularly in relation to the aftershocks of colonization, displacement, and war.

I work primarily with film and installation. Oral histories, personal and collective narratives, and site-specific landscapes are central to my process. Many of my works begin with listening — to people, to places, and to silences.

Projects such as Khudoi (2024–present), Hafta (2024), Apat (2023), Hazm Kardan Dushvor Ast (2020), Return Policy (2019), and Qyrqy (2018) all address, in different ways, questions of loss and continuity. They speak about what has disappeared, what has been erased or silenced, and what continues to survive in fragments — through voice, landscape, or memory.

For example, Hafta is a seven-part video work that reflects on extinction and the successive episodes of Central Asia’s colonization, using a partly fictional, intergenerational narrative of women. Other works focus more directly on mourning practices, borders, environmental trauma, or the politics of return and displacement. Together, these projects form a kind of archive — one in which history is felt rather than illustrated.

My recent works also include Pas az Sukuti Dastarkhon, a sculptural video installation reflecting on loss through voice. While my practice is research-driven, it remains deeply personal.

LP: Can you share your experience participating in the Venice Biennale as the only artist representing Tajikistan? How did the selection process unfold, which work did you present and what is it about, and what did this milestone mean to you personally?

NK: My participation in the Venice Biennale took place through the Biennale College Arte open call, a program for artists under 30. Each edition, four artists are selected from an international open call to participate in the main exhibition of the Biennale. I applied through this process, and Hafta was ultimately selected.

Hafta is a seven-channel video installation commissioned for Foreigners Everywhere, curated by Adriano Pedrosa. The work addresses the idea of extinction and the processes that have led to the near disappearance of water resources, fauna, and local languages.

In Hafta, I intertwine the collective history of the region with my own family history. My ancestors were forced to flee their native Kazakhstan in the 1930s in search of survival during a period of violent modernity. This personal trajectory became a way to speak about broader historical ruptures.

Technically, Hafta consists of seven screens, each dedicated to one of the seven women — mothers — from my lineage. In many cases, concrete biographical information about these women no longer existed or had been lost. Where history and archives failed, I turned to fiction as a method. Inventing these stories became a way of repairing historical silence.

During the making of the film, I travelled from Kazakhstan to the place of my birth and then back again, retracing the path of my ancestors. Through this journey, I connected the physical landscapes of my motherland — its dried-out steppes and lost waters — with the virtual space of the moving image. The seven video channels are installed in a way that allows the viewer to witness a gradual return of water to Central Asia as the work unfolds. Symbolically, justice is restored to the women who preceded me, and broken connections are repaired. As water returns to the land, the women of my family also find their way back home, suggesting that a different future may still be possible.

As for my impressions of participating in the Venice Biennale — it was, and remains, an exciting and transformative experience. It pushed my practice and career forward in a very tangible way. And, in fact, you will see me in Venice again next year, so please stay tuned.

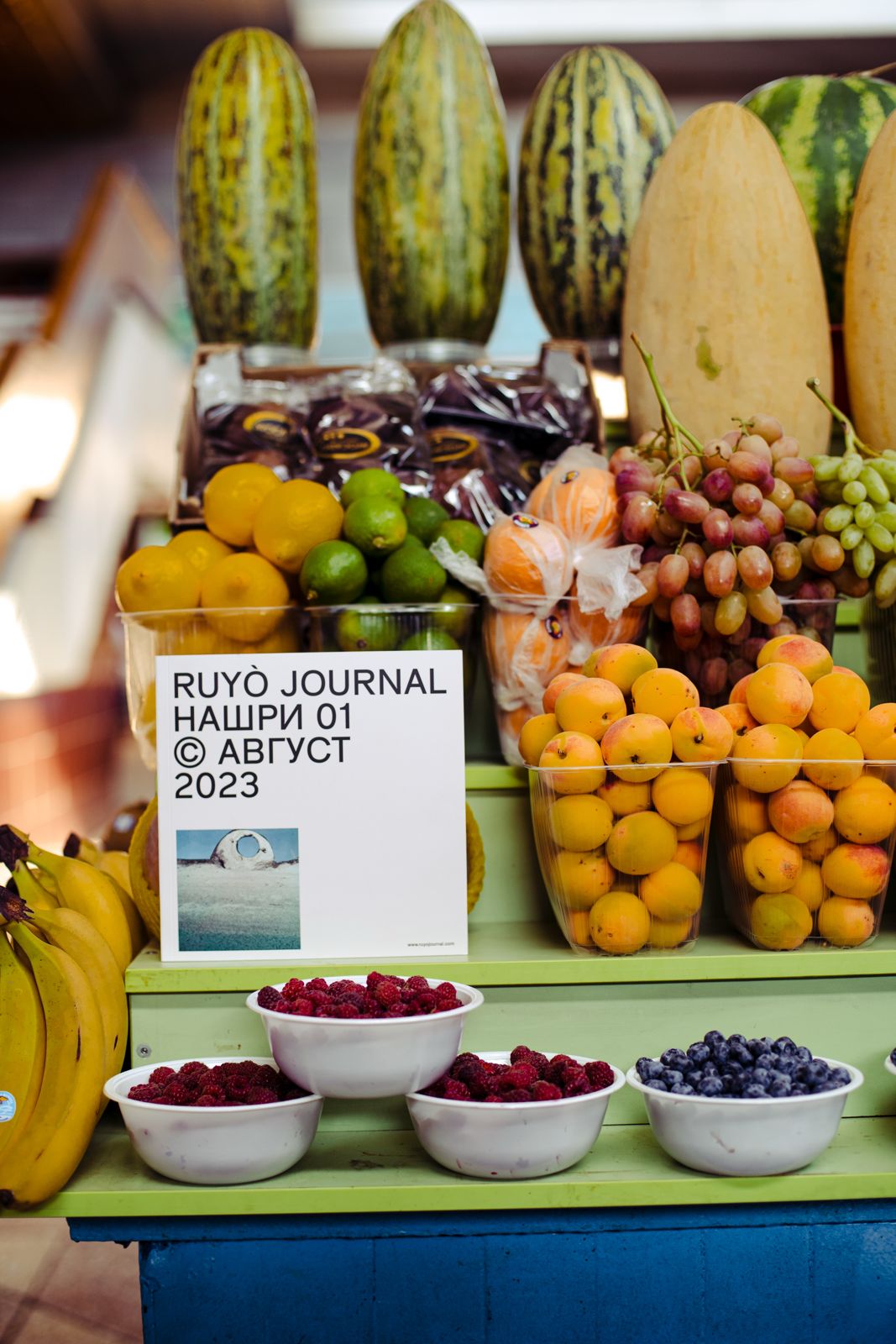

LP:You’ve been co‑publishing Ruyò with Sabina Khorramdel since 2022. How did this collaboration start, what is the journal focusing on now, and how do you see its future?

NK: My editorial practice actually began earlier than 2022. From 2017 to 2019, together with fellow artists, I co-ran HORSEMILK, an independent platform dedicated to Central Asian contemporary art and culture. It was during this time that I began to understand publishing as a form of artistic and political practice.

Ruyò was later co-founded together with Sabina Khorramdel and Samaya Böhmer. We all come from Dushanbe, attended the same school, and have been close friends for many years. Our collaboration emerged from a shared sense of urgency to create something independently, outside of institutional frameworks. Ruyò is a self-publishing, independent initiative.

At the moment, the journal is very active. This year, we published two printed editions and are currently working on a poetry book as well as a third issue. For us, Ruyò is an evolving platform where publishing becomes a way of thinking, archiving, and collectively imagining futures.

We want to continue experimenting with formats, supporting emerging voices, and building long-term dialogues. It is a slow and careful practice, and I believe that this slowness is precisely its strength.

So yes — please follow our work. We are only just getting started.

LP:You were recently in London as part of a residency at Delfina Foundation and have also participated in the Bukhara Biennial. Could you tell us about your research and plans during the residency, as well as the work you presented at the Biennial?

NK: Thank you for your patience with this interview. At this point, I am already back in my studio in Almaty, having completed my residency at Delfina Foundation in London, as well as both the opening and closing of the Bukhara Biennial.

During my time at Delfina Foundation, I continued working on my research into the civil war in Tajikistan. The residency was extremely precious to me, offering time, care, and a supportive environment for research. Delfina was a generous experience both intellectually and emotionally, and I hope that the connections formed there will continue into the future.

For the Bukhara Biennial, a new work of mine was commissioned by ACDF. The work is titled Pas az Sukuti Dastarkhon (After the Silence of Dastarkhon). It is an installation that focuses on the moment after a funeral end — when the guests have left, the room exhales, and the first quiet processing of loss begins. Rather than addressing loss as a public ritual, the work turns toward its most intimate and fragile continuation.

This project was developed in close collaboration with Jonon Zulaikho, Gulrukh Norkulova, Mehriniso Samieva, Rustamdjon Tagaykulov, and Masudjon Madaliev. This collaboration is what makes the work especially dear to me, and I hope we will continue working together in the future.

At the moment, I cannot yet share further details, but there are plans for the work to be exhibited again in 2026.

Lolisanam Ulugova is an independent film and theatre producer, curator, and art journalist. She holds a Master’s degree from the University of Turin and an Erasmus+ Choreomundus International Master in Dance Knowledge, Practice, and Heritage. A former Global Cultural Fellow at the University of Edinburgh and a CAAFP Fellow at George Washington University, she has contributed to Voices on Central Asia, The Diplomat, and Curator Space. Her artistic work addresses violence, inequality, and marginalized voices through theatre and film.