By Agha Iqrar Haroon

The recent visits of the Presidents of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan to Pakistan have once again brought the issue of Pak-Afghan border trade into sharp focus. Both Central Asian states are banking on rail and multi-modal connectivity with Pakistan through Afghanistan, viewing Pakistan’s ports as their most viable access to global markets. In particular, Uzbekistan’s trade with Pakistan remains heavily dependent on transit routes passing through Afghan territory.

This strategic emphasis was clearly reflected in the joint communiqué issued after talks between Pakistan and Kazakhstan and Pakistan-Uzbekistan. After the talks of Pakistan and Kazakhstan the two countries reaffirmed their strong commitment to promoting international multimodal transport corridors linking the two countries through routes including Kazakhstan–Turkmenistan–Afghanistan–Pakistan, Kazakhstan–Uzbekistan–Afghanistan–Pakistan, and Kazakhstan–Kyrgyzstan–China–Pakistan. Pakistan welcomed President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev’s initiative to connect Central and South Asia through the proposed Trans-Afghan Railway Corridor. Both sides directed relevant authorities to evaluate the feasibility of developing the Kazakhstan–Turkmenistan–Afghanistan–Pakistan railway line.

Similarly, the Pakistan-Uzbekistan joint communiqué underscored the centrality of regional connectivity for economic integration, transit trade, and socio-economic development. The two leaders welcomed the signing of the Framework Agreement for the Uzbekistan–Afghanistan–Pakistan (UAP) Railway Project on July 17, 2025, in Kabul, and reiterated their commitment to the project’s early completion. They also endorsed the Termiz–Kharlachi route for the UAP railway and agreed to jointly finance its feasibility study, expressing hope for its early finalization.

In addition, both sides welcomed the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding on Multimodal Transport in September 2024, aimed at facilitating seamless transit and trade connectivity between Pakistan and Uzbekistan. Pakistan reaffirmed its readiness to provide access to its seaports for Uzbek transit cargo and to make available its international-standard road network to support Uzbek trade needs. These commitments reflect a shared vision of deeper economic integration and more efficient, reliable, and cost-effective transport links across the region but not without going through Afghanistan.

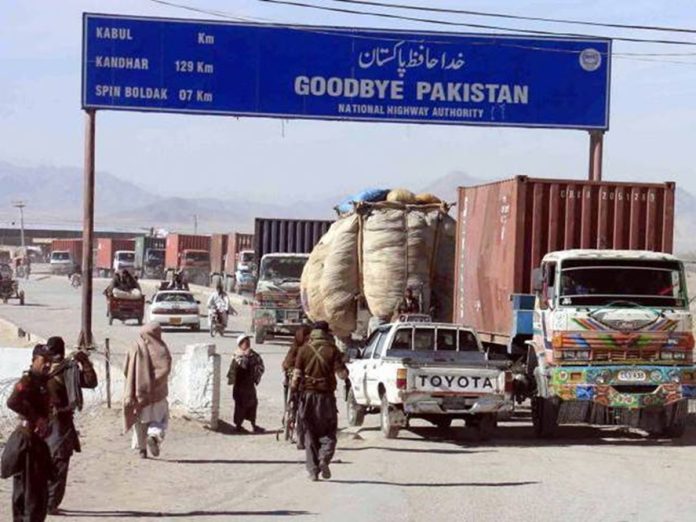

However, these ambitious connectivity plans expose a glaring contradiction in regional policy. While Pakistan remains engaged in discussions on Pak-Afghan trade and transit, it has repeatedly closed its border with Afghanistan due to serious security concerns. Meanwhile, although Pakistan and Kazakhstan also discussed the Kazakhstan–Kyrgyzstan–China–Pakistan route that bypasses Afghanistan—most of the proposed multimodal corridors and railway projects with Central Asian states remain impossible without transit through Afghan territory.

This reality raises several critical questions that Pakistan cannot afford to ignore.

First, is Pakistan prepared to reopen border trade with Afghanistan despite persistent allegations that Afghan soil is being used to harbor, finance, and export terrorism into Pakistan?

Second, are Central Asian states willing or able to provide credible guarantees that Afghan territory will not be used as a conduit for militant infiltration under the cover of expanded trade and transit?

A third, albeit longer-term, option for Pakistan could be to wait for a political transformation in Afghanistan, specifically, the emergence of an inclusive government in Kabul in line with the Doha Peace Accord before fully reopening transit and trade.

The regional context further complicates Pakistan’s position. Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan appear reluctant to rely on the Pakistan-Iran route due to ongoing U.S. sanctions on Iran. Consequently, their flagship regional projects such as TAPI, CASA-1000, and proposed railway project continue to revolve around Afghanistan. Even recent diplomatic initiatives like the Termez Dialogue, hosted by Doha and led by Uzbekistan, have strongly promoted trade connectivity with Afghanistan. This suggests that alternative routes like Kazakhstan–Kyrgyzstan–China–Pakistan are not the first preference of Central Asian states.

As a result, pressure is mounting on Pakistan to relax restrictions on Pak-Afghan trade. Certain Gulf countries have reportedly urged Pakistan to maintain economic engagement with Afghanistan. Their argument is that Afghanistan’s economy is rapidly deteriorating due to the prolonged closure of trade routes, especially along the Pakistan border.

Ultimately, Pakistan finds itself caught between regional connectivity aspirations and hard security realities. While economic integration with Central Asia offers undeniable strategic and commercial benefits, reopening transit routes without robust security assurances risks undermining Pakistan’s internal stability. Any sustainable policy must therefore balance economic diplomacy with uncompromising national security safeguards—an equilibrium that remains elusive under the current Afghan dispensation.

Disclaimer:

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official policy, position, or editorial stance of The London Post.

Any assumptions, interpretations, or conclusions drawn in the analysis are those of the author alone and should not be attributed to The London Post as an organization.